Before We Think: Culturally Encoded

𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐂𝐮𝐥𝐭𝐮𝐫𝐞 𝐋𝐞𝐧𝐬 (𝟑) : On the invisible codes of culture that shape our worldviews long before memory or reason.

Last week, we picked up our 5-year-old son from his public kindergarten in Beijing. On the way home, he proudly recited a Tang Dynasty poem by heart — 春望 (Chūnwàng, or Spring View, 757 AD), one of the most famous and widely recited works from that vibrant dynastic era over a thousand years ago, written by the renowned poet 杜甫 (Dù Fǔ, 712–770). The poem reflects on wartime and exile — hardly light or child-friendly themes. But that’s not the point. Children (and adults) recite ancient poems not just for their content, but for their rhythm, rhyme, tone, and the cultural feeling embedded in them.

This is how cultural programming begins: not through rules or explanations, but through patterns of sound, expression, emotion, action, and symbolism absorbed long before we are aware of them.

Source Wikipedia including details about the structure, genre and context of the poem. Translation by Stephen Owen, American sinologist specializing in Chinese literature, particularly Tang dynasty poetry and comparative poetics. He taught Chinese literature and comparative literature at Harvard University.

The Culture Lens : A Collection of Essays

Culture is often discussed in the context of international business or travel—linked to etiquette, negotiation styles, traditions, or “do’s and don’ts.” But culture runs deeper. It shapes the foundations of society and informs how people understand the world around them.

In diplomacy, social relations, and geopolitics, cultural differences are frequently overlooked or approached with limited tolerance. Yet culture lies at the heart of why people act, react, and think the way they do—and why perceptions of one another diverge, particularly between China and the West.

The Culture Lens collection brings together a series of essays and reflections on how different societies perceive and interpret each other—socially, politically, and economically. Drawing on cultural models and paradigms, these pieces explore how deep-seated worldviews influence contemporary affairs, business relations, and public discourse.

This ongoing essay series aims to make sense of sensitive issues and complex developments in bilateral and multilateral relations—through the lens of culture, and with the goal of fostering greater mutual understanding.

Between Understanding and Being Shaped

From the moment a child is born, they are immersed in a world shaped by specific values, social codes, daily rhythms, and unspoken assumptions. This early immersion is what we call cultural programming — a term introduced by Dutch sociologist Geert Hofstede. He described culture as the “software of the mind”: deep, invisible coding that influences how we think, act, and interpret meaning (Hofstede, 2001). Even if you live in another country, speak its language fluently, and study its customs, there remains a core difference between understanding a culture and being shaped by it. Cultural programming can be built upon, but never fully replaced.

That shaping begins at birth — or even earlier. Behavioral geneticist Robert Plomin notes that temperament and cognitive sensitivity, which influence how children learn and respond to their environment, are at least partly heritable (Plomin, 2018). This means cultural programming isn’t just learned; it may also be reinforced by inherited dispositions that align a child with the values and expectations of their cultural setting.

This becomes especially clear when we look at cultural transitions between profoundly different civilizations — such as East Asian societies like China and the Germanic or Anglo-Saxon cultures of Europe and North America. Despite increasing globalization, the cultural DNA of these societies remains deeply distinct. A foreigner living in China may become fluent in Mandarin, study Chinese history, grasp the influence of Confucian or Daoist thought, and immerse themselves in society. Yet the emotional instincts and reflexes shaped in early life — how one responds to authority, ambiguity, success, setbacks, shame, or praise; how one argues, apologizes, or interprets silence — often remain rooted in the cultural code of one’s upbringing. One can perform another culture, but it’s much harder to feel it in the same instinctive way as someone born into it.

Culture as Cognition and Evolution

In East Asia, including China, and in the West, people often think differently—not just act differently. Western cognition tends to be analytical and focused on discrete categories, while East Asian thinking is more relational, holistic, and context-aware (Nisbett, 2003). These are not just surface-level preferences; they shape everything from how problems are framed to how social harmony or disagreement is approached.

Whereas Chinese thinking often follows a cyclical, process-oriented path, Western thinking is more linear and goal-driven.

Cultural programming, then, is not only about beliefs or behaviors, but about mental framing—what we pay attention to, what we filter out, how we interpret uncertainty and change, and even what we consider a “problem” in the first place.

Mental framing is deeply rooted in foundational cultural tools—such as the structure and learning methods of language, mathematics, and number systems. While it is widely recognized that the Chinese language differs significantly in structure and expression, numerical systems in China also reflect a distinct mental orientation. Chinese thinking operates in units of 万 (wàn, ten thousand) and 亿 (yì, one hundred million), rather than thousands and millions as in many Western contexts. Similarly, ancient Chinese mathematics prioritized algorithmic approaches geared toward practical computation, whereas Greek mathematics emphasized formal proof and abstract reasoning.

Beyond language and number systems, cultural programming is also deeply shaped by how societies perceive the purpose of education, conceptualize time, and construct calendrical systems and cycles. Similarly, legal and ethical frameworks—shaped and reshaped over centuries—inform collective notions of justice, fairness, and appropriate behavior. In doing so, they embed culturally specific patterns of reasoning and judgment into the routines of daily life. All these elements reflect distinct civilizational rhythms and priorities.

This view is echoed in the work of Joseph Henrich, who argues that human evolution is as much cultural as it is biological. The practices and norms passed down through generations—from child-rearing to conflict resolution—are not merely social habits. They are evolved systems of knowledge, survival, and intelligence embedded in cultural life (Henrich, 2016). Disrupting or discarding them without understanding their purpose can lead to unintended consequences.

This becomes especially relevant when observing the rise of so-called “woke” discourse in various Western societies. Anglo-Saxon cultures—and to some extent, Germanic ones—have long emphasized the individual. Enlightenment ideals, Protestant ethics, and liberal political thought have reinforced values such as autonomy, self-expression, and individual rights. I recall being encouraged as a child to "find myself," to pursue my own path and ambitions—ideals that are not seen as disruptive, but rather as meaningful pursuits within a stable cultural framework. That framework is shaped by deeper codes of tradition, identity, and the contextual influence of family, society, or religion.

In recent decades, however, this framework of cultural programming in Western societies has experienced significant fragmentation and disruption. Movements sometimes labeled as “woke” have emphasized individual experience and inclusivity, increasingly at the expense of more traditional and long-standing social structures. While this shift may stem from a genuine concern for justice and freedom, it can also lead to a weakening of inherited cultural codes. Children growing up in such environments may receive mixed signals: encouraged to honor diversity, yet also to define their identity independently; urged to question norms, yet expected to conform to new and often fluid social expectations.

This contrasts sharply with the cultural programming in China (and other East Asian cultures), which is based on civilizational continuity. Rooted in thousands of years of Confucian, Daoist, and Legalist thought, Chinese society has developed a dense web of expectations around social roles, collective identity, and hierarchical order. Cultural values such as filial piety, harmony, and face (miànzi) are not recent inventions—they are inherited through generations and embedded in language, rituals, family norms, and educational systems. A child in China is not simply taught how to behave; they are immersed in a worldview where the self is always seen in relation to others.

Picture 天坛 (Tiāntán, Temple of Heaven), Beijing, China by Quan Jing (Unsplash)

But cultural programming is not static. It evolves—gradually and unevenly. In China, while traditional values remain deeply influential, contemporary forces such as consumerism, digital culture, and globalization are reshaping how younger generations express themselves. Yet this change tends to be layered over the deeper cultural structure rather than replacing it. A Chinese teenager on social media may appear “Westernized,” but their emotional responses—to joy, shame, duty, or authority—often remain distinct from those of their Western peers.

And that’s perfectly fine !

Deep Codes and Diverging Paths

In today’s deeply interconnected world, it is increasingly important to understand others’ cultural programming—not just what people in other cultures say or do, but why they act that way. This means grasping the underlying purpose and thought processes embedded in cultural codes rather than projecting our own cultural programming onto their behaviors.

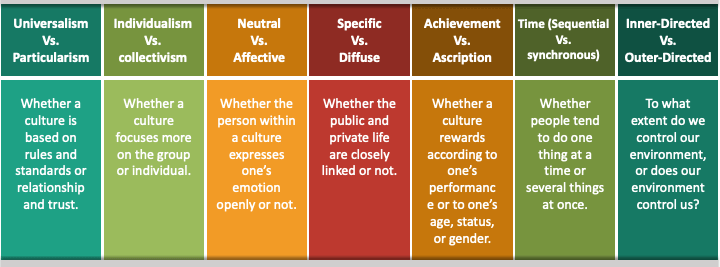

Fons Trompenaars’ model of cultural dimensions provides a useful framework for this deeper understanding, moving beyond cultural markers like negotiation tactics or etiquette. Dimensions such as Individualism versus Collectivism, Universalism versus Particularism, and others offer insight to subconscious logic behind behavior. While these cultural dimensions evolve over time and shift along a continuum, they rarely flip entirely. They shape behavior patterns deeply in different cultures, especially those formed in early childhood.

Trompenaars 7 cultural dimensions

Returning to the fragmentation and disruption of cultural programming in some Western societies (“woke” discourse as some call it)—particularly through the lens of Trompenaars’ framework—one can observe a drift toward more extreme ends of cultural dimensions, notably individualism and universalism. This kind of cultural extremism tends to erode the capability to empathize with, or even recognize, the opposite ends of these cultural dimensions—both within one’s own society and across cultural boundaries.

Every culture encodes a blend of opposing cultural values—such as Universalism versus Particularism, or Individualism versus Collectivism—though with differing emphases. Cultural extremism arises when one pole becomes so dominant that the other is marginalized or dismissed, disrupting the balance of cultural codes in one’s own society and straining relationships with cultures that emphasize different values. Another example can be found in China during the 1970s, when the Cultural Revolution pushed the society toward a radical form of collectivism. As history shows, pulling cultural plugs too radically or dismantling long-standing codes often foreshadows turbulence.

Trompenaars’ framework also offers valuable insight into the current global transformation and the dynamic shifts toward a multipolar world order—particularly in understanding China’s role. It helps illuminate key questions often asked in international discourse: How did China achieve such rapid modernization and innovation to become a moderately prosperous society? Is China actively seeking to dominate or reshape the world order? And amid ongoing geo-economic tensions and tariff wars, who is truly isolating whom?

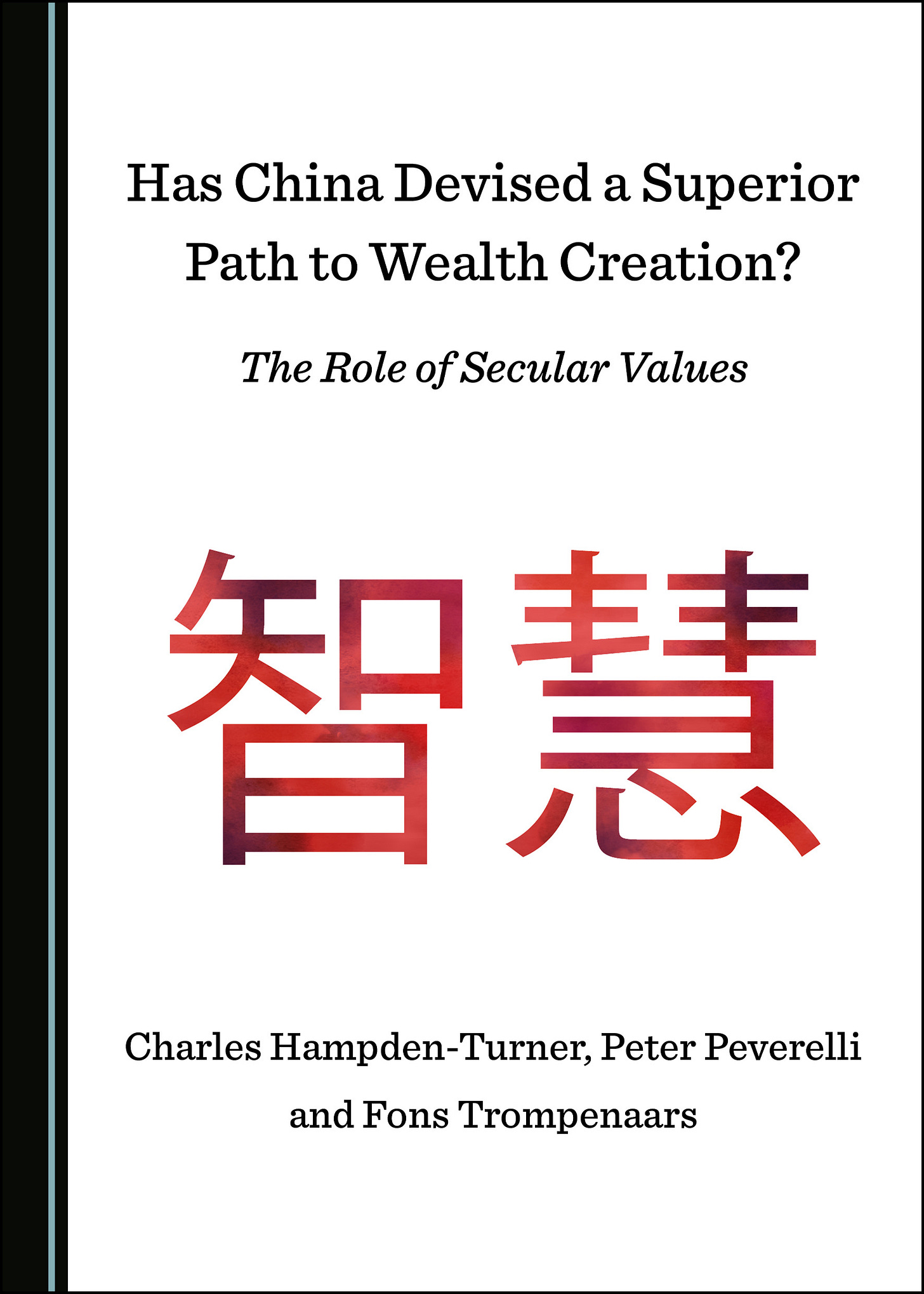

For a more in-depth exploration, the book Has China Devised a Superior Path to Wealth Creation? The Role of Secular Values (2021, Hampden-Turner, Peverelli & Trompenaars) offers a comprehensive analysis of these and other questions through the lens of Trompenaars’ cultural dimensions model.

Living Between Cultural Rhythms

Why am I so invested in Chinese culture? Beyond having a family here, I simply feel at home in China and within Chinese society. That sense of comfort and belonging fuels an ongoing curiosity. Understanding and immersing in cultural programming is central to this rewarding mental journey of discovery—and a journey of self-awareness, recognizing when my own cultural codes influence my thoughts and reactions. Usually these codes align well, but occasionally they cause confrontation when I’m reminded, sometimes uncomfortably, of the limits and biases within my own cultural programming. And at other instances, it works the other way around—where aspects of my cultural imprint challenge codes and values I now live within.

This isn’t about right or wrong. Cultural programming — with all its invisible codes — has simply evolved differently across civilizations, shaped by historical eras and experiences. And it continues to evolve, requiring constant and subtle care to preserve the balance and integrity of unique cultural codes, while guarding against sprouts of cultural extremism.

At its core, cross-cultural understanding doesn’t demand that we become the other. It begins with humility — acknowledging that others are shaped by different cultural codes, from birth or even before. Respect isn’t assimilation.

It means recognizing the programming within ourselves and others — and appreciating that something as simple as a thousand-year-old poem, memorized in early childhood, can carry the weight of an entire civilization.

It means reflecting critically on our own cultural programming and becoming conscious of the different codes that shape other cultures. After all, the software of the mind in each culture has not been written by formal rules, but by evolving patterns of sensory and emotional experience — practices that transmit and evolve knowledge, instinct, and intelligence over time.

It means understanding that we have more in common than we might think — and that the diversity of cultural programming enriches human evolution. Instead of fragmentation or polarization, it offers the possibility of balancing the scales of cultural spectrums, expanding our collective capacity to learn, adapt, and thrive.

As a grateful immigrant, I feel humbled watching our son be shaped by the rhythms and rhymes of Chinese culture, complemented by the positive influence of my own cultural imprint. While I’ll never live Chinese culture with the instinct of someone born and raised into it—and nor is that the goal, being a native of the specific and beautiful culture of Limburg in the south of the Netherlands—I did catch a small slip in his recital: he confidently credited the poem to the wrong Tang Dynasty poet. Clearly, ancient poetry features regularly in their kindergarten routine—enough for even the mix-ups to be performed with flair.

Maybe one day I’ll draft a detailed outline of arguments to explain why I feel at home in China. But as I write this sentence, I realize that very impulse—to explain, to conclude—reflects codes of my own cultural programming. Why the urge to define an endpoint, when what truly matters is the unfolding of the journey itself?

What nurtures deeper learning and gratitude: the destination, or the way itself?

May 24, 2025

Gordon Dumoulin

References

Henrich, J. (2016). The Secret of Our Success: How Culture is Driving Human Evolution, Domesticating Our Species, and Making Us Smarter. Princeton University Press.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture's Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

Nisbett, R. E. (2003). The Geography of Thought: How Asians and Westerners Think Differently... and Why. Free Press.

Plomin, R. (2018). Blueprint: How DNA Makes Us Who We Are. MIT Press.

Trompenaars, F., & Hampden-Turner, C. (1997). Riding the Waves of Culture: Understanding Diversity in Global Business. McGraw-Hill.

I agree about the programming, having worked in many countires and cultures. in Africa and East Asia... When I realized this was one day inSomalia I saw a woman dressed not like Somalia women are, who though Muslims do not always cover their hair or face, but this one was ALL Covered, I could not even see her eyes, she was in Black... and walked in the sun, Mogadishu has a 99.9% level of humidity... she walked rapidly... I looked at her and thought... well for her its no doubt her way, its natural, she was brought up that way... and that is where I reaiized she is programmed to think like that just like... The Somali women are programmed to do whatever they do and I OMG ME TOO I am programmed to do and think and behave like expected of a Danish Woman.... ... etc etc... AND...

Now at 84 and retired after working for 45 years in Africa and East Asia... with Social work... its reather painful to see how intolerant our politicians are, and how they manipulate and play on the differences between out native Danish population and the people who moved here for various reasons, mostly due to wars (we were part of provoking BTW)... Where I see and know our similarities and I rather like seeing all the different looking people ... that I am used to... so used that I ouatomatically speak in English to them... only to find some of them are 2nd generation they were born here and speaks even better Danish than I do ... etc etc etc I could write books about it... anyway I think all these people who came from other countries, cultures, religions etc are an enrichment... not sometthing we should be afraid of... we should get to know one another, and respect oneanother...

AND BTW... am currently watching a Russian series on Peter The Great... and learning how Russians

see their history and that of Europe and the whole world at his time... and compare with what I learned in School ie how Danes learn to see the world at that time... again not just programming... but in the case of Denmark what we don't learn.... WOW.... no wonder there are wars.

Let’s rewrite what they forgot:

Wealth is who you hold.

Profit is peace you sold.

Legacy is love untold.

https://thehiddenclinic.substack.com/p/the-lost-ledger