Cultural Tapestry: Weaving Democracy's Fabric

𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐂𝐮𝐥𝐭𝐮𝐫𝐞 𝐋𝐞𝐧𝐬 (𝟐) : Chinese versus Western Democracy through Cultural Dimensions

Culture Lens : A Collection of Essays

Culture is often discussed in the context of international business or travel—linked to etiquette, negotiation styles, traditions, or “do’s and don’ts.” But culture runs deeper. It shapes the foundations of society and informs how people understand the world around them.

In diplomacy, social relations, and geopolitics, cultural differences are frequently overlooked or approached with limited tolerance. Yet culture lies at the heart of why people act, react, and think the way they do—and why perceptions of one another diverge, particularly between China and the West.

The Culture Lens collection brings together a series of essays and reflections on how different societies perceive and interpret each other—socially, politically, and economically. Drawing on cultural models and paradigms, these pieces explore how deep-seated worldviews influence contemporary affairs, business relations, and public discourse.

This ongoing essay series aims to make sense of sensitive issues and complex developments in bilateral and multilateral relations—through the lens of culture, and with the goal of fostering greater mutual understanding.

This essay discusses the cultural dimensions of Chinese versus Western democracy based on Chapter 9 of the book: Has China Devised a Superior Path to Wealth Creation? The Role of Secular Values. In this chapter, most of the Western criticism that China is not a democracy is analyzed and refuted using the 7-Dimension (7-D) model of national culture developed by Fons Trompenaars.

Trompenaar’s cultural dimension model has been explained in detail in the recent China21 Journal essay ‘it’s the culture, stupid !’ with an attempt to enhance the cultural understanding of why and how is China doing what and when.

'it's the culture, stupid'

Culture is the cradle for prosperity or survival as a nation, society or people’s identity. The states of economy or political governance are continuously subject to change with ups and downs. But culture explains how different nations, civilizations and its people deal with these ups and downs, and therefore shaping its own and other’s prosperity, survival or destruction.

Is China a Democracy ?

Almost nothing hurts China more than the accusation that it is not a democracy and has no intention of becoming one. This accusatory assumption is deeply troubling to the world for several reasons.

First of all, China represents a large part of the world's population with one and a half billion and thus suggests that democracy, literally: the influence of the people (demos in Greek) on the day-to-day management (kratein) of their living environment, is not attainable for a significant portion of people in the world.

Secondly, the West has gotten used to the idea that democracy and prosperity go hand in hand. However, the economic success of a supposedly undemocratic China in recent decades has proven otherwise.

Thirdly, China's astonishing growth is likely to be emulated by other emerging economies, and they may increasingly question whether it is in their interest to comply to constant Western pressure to become ‘more democratic’. The cornerstone of Western economic orthodoxy that economic success can only originate from ‘freedom’ and ‘democracy’ seems to be faltering by China’s economic success story. Western economists are confused and Western politicians are anxious.

But instead of analyzing and studying China’s economic rise, politicians and media in West preferably deny and have turned to their so-called ideological values of democracy in efforts to portray China increasingly negative as fearsome. More ideologically as China’s economic rise has pulled ‘the democracy narrative as the only necessary condition for economic success’ from under the rug.

Discernment of Conflict in Democracy

Western democracy assumes that the people are in conflict over the proper form of government and that this should be debated orally without violence or threat of violence and that the debate is won by one side and lost to all others. The majority on any subject must be given the opportunity to govern and carry out its way of running the country, municipality, etc. Voters vote for or against those who conduct these debates, depending on their own personal judgment. The idea is to move from division to an agreement by at least a majority.

The Chinese strive for unity, but know that to achieve this, some division is inevitable, as long as it can be controlled. We can well imagine the reasons for this. The world's largest population is all too easily divided. Growing rice requires cooperation from the whole community, and without such cooperation, there will be famine. Historically, famine usually led to civil wars. Indeed, the Chinese are haunted by the prospect of disorder. It's their nightmare. Incidentally, Western states also retain the monopoly of lawful violence. They will suppress riots, as the U.S. has regularly shown in their society, and many democracies would have ended the kind of disorder witnessed in Hong Kong in 2019 in a much shorter period of time than the Hong Kong authorities have done. Let's map this out.

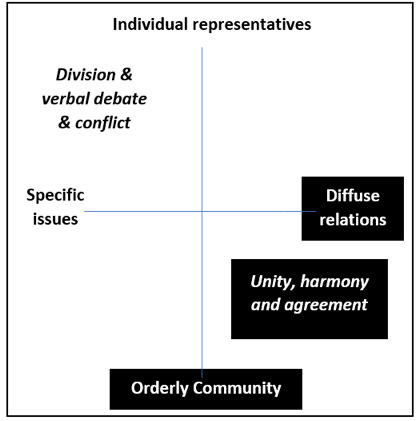

The West promotes division and verbal debate and conflict, in which individual representatives debate specific issues on which rival parties have opposing views. They are unlikely to reach complete unanimity or agreement, but at least the majority will get their way and in the years to come there may be wider agreement. We can see this in historical and more recent developments in different Western countries such as the women’s right to vote, tolerance of homosexuality or the abolition of the death penalty.

China, on the other hand, relies on unity, harmony, and agreement. A process which takes place in the midst of diffuse relationships within an orderly community. The big question here is the amount of space to ventilate and discuss conflicts to reach consensus. Read more in the next chapter about negotiations to consensus, more space for discussing conflicts will influence consensus in depth and time.

We surprisingly witness this dynamic especially in the West these days. In the light of major disputes such as the wars in the Ukraine and Palestine, expressing conflicting views against the ruling forces are increasingly less permitted or readily dismissed, both in governance chambers and in the people’s streets. Firm unity and tight knit agreement are top priorities for those in charge approaching these major disputes.

Discernment of Consensus in Democracy

There are at least two essential aspects of democracy. One of these is to elect a leader and/or policy proposal through elections, so that the leader/policy is supported by a majority of the electorate. The second is to reach a negotiated consensus on a number of key issues.

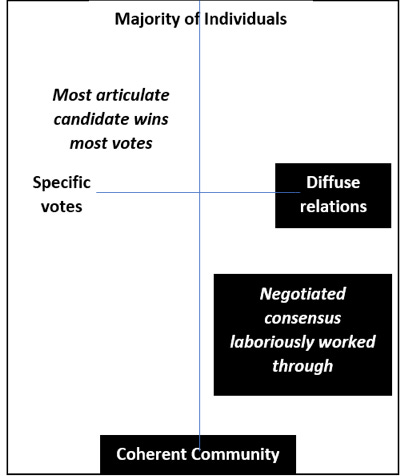

The West opts for elections and defeating opposition parties, while negotiated consensus is most desired in the East. The Western way does not always lead to desired results for humanity. After all, Adolf Hitler also came to power through elections. An elective dictatorship has no value and voting for one's own tribe and religion does not contribute to democracy. America tends to institute elections in regions it has gained control over as soon as possible, as in Vietnam or Iraq, but where the electorate elects an intolerant clique, little is gained. There is no point in winning the election if you then attack all those who are against you. Again, we can map this using cultural dimensions.

In the upper left quadrant, the most eloquent candidate wins the largest number of votes. Pericles, the spokesman for Athenian democracy, was brilliantly eloquent. The benches in the British House of Commons are two sword's lengths apart.

On the other hand, we have a coherent community of people who are connected to each other through diffuse relationships. This leads to a consensus negotiated down to the last detail. Much of this is invisible and takes place behind the scenes. Where this consensus is broad and inclusive, much better decisions can be made and it is no surprise that many Asian economies are of this type. A high-quality product is well-designed, inexpensive to manufacture, easy to maintain, attractive to look at, economical to use – all of these qualities must be negotiated among experts and require nothing less than consensus.

The advantage of consensus is that more people are involved and dissenting voices can take into account their specific objections, while those who are outvoted in Western democracy lose their votes.

What Cultures Do and Don’t Show

Cultures tend to showcase what they are proud of and leave behind the scenes what they don't like. This adds to the hostility the West feels towards China.

For example, when we see hundreds of people wearing similar dark suits clapping in straight rows at a speech by their president, this strikes the West as an example of a solitary leader who does not tolerate any opposition.

However, if this is true, why are so many Chinese decisions of such high quality? How could they eradicate so much disease and poverty? Why is their economy growing so fast? For the Chinese, dutiful applause means agreement, consensus, order, loyalty, and harmony about where the country is heading for. The nation is moving forward in unison toward greater prosperity and global leadership.

To some extent, the image of applauding officials is deceptive, because the Chinese People’s Congress applauds what has already been decided. The purpose of the meeting is not to make decisions, but to celebrate decisions that have already been worked out behind closed doors. Yes, there is indeed a consensus, but it has been hard-won through very difficult negotiations. Behind the scenes, there was fierce disagreement, until an agreement was finally reached. These fights took place in the corridors and in private meetings. Because the Chinese admire consensus and loathe conflict and disorder, only the consensus is shown to the general public. Chinese citizens know that the applause is a genuine relief that consensus has been reached after such difficult negotiations. We will map this once more.

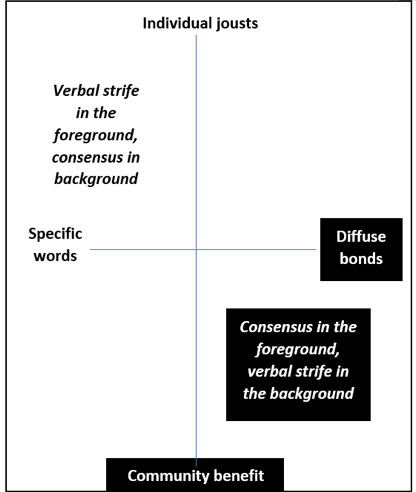

Western democracy is a combination of individual fights and specific words, used largely for dramatic effect, as in the theater. It is no coincidence that the term democracy originated in a nation with a strong theatre culture. It leads to the upper left quadrant: verbal battle in the foreground, consensus in the background. Both parties respect the parliamentary procedure.

In contrast, a combination of diffuse relationships and common interests leads to the lower right quadrant: consensus in the foreground, verbal struggles in the background. Every culture flaunts what it is proud of and hides what it is less proud of.

There are, of course, big differences in style. Battles waged in public are exaggerated for theatrical effect. In battles that are kept private, mutual respect can be maintained. We all know that the negotiations go badly when their contents are leaked to the press. In a jury trial, the trial must be public, but the jury deliberates in secret. All systems of human organization are a mixture of both.

This can also be seen in business environments. In the West, a meeting is called to discuss an issue and many attendees get the floor. All disagreements are expressed, even if no decision is taken at the meeting. In any case, the decision-makers know all the opinions.

In the East, a meeting is called to announce an agreement and those present are expected to approve, applaud and implement it. They may have been prior and personally consulted in the process of reaching that agreement, depending on how influential they are. It's less of a hierarchy than an inner circle. If you do still disagree with something during the final meeting, you will ruin the spirit of excitement.

Particularistic Democracy - a Real-life Case

Someone asked on Quora if Chinese people wouldn't prefer to live in a democracy.

Here's an interesting answer.

I live in Beijing. One day in the winter of 2022, I went out of home for shopping and found in the street adjacent to my community, there’s a pile of sand occupying the sidewalk. It seems to block the way and I had to step down the road shoulder to bypass it.

I called 12345, a kind of mayor’s hotline, and reported to the receptionist about what I witnessed. Then forgot (about) the call.

The next day a man, who said he is the officer of the community committee, called me that they’ve solved what I complained to (the) 12345 hotline. The pile of sand had been removed. He pleaded me to double-check when available and if everything is OKAY, don’t forget when 12345 is calling back to me for the result, pls tell them everything has been down on time.

At the afternoon, 12345 really called me back. I told them I have double-checked and the sands had been removed. The receptionist then asked me if I’m satisfied (with) the result or not. Of course, I said YES. Nothing to complain more.

So I don’t know if this is a democracy or not? I’m just a average person. A citizen. Not a(n) officer or powerful guy or rich guy or CCP member at all.

I don’t know how do you define democracy. If it means all those old guys quarrelling in the parliament house, fighting for the seats and elections, then No, in China it seems to lack these sorts of things.

But if democracy means that the suggestions from an average person could be respected and kindly treated, its reasonable parts will be accepted and improved, then Yes, I got it.

Many of our Chinese friends and acquaintances living in China have similar experiences.

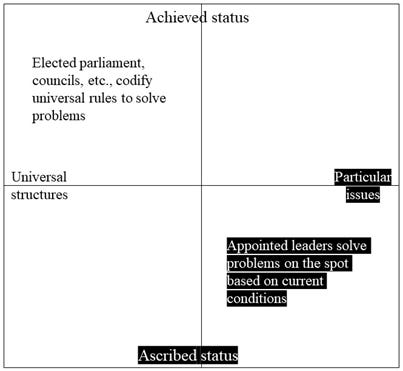

What is going on here in terms of cultural dimensions? In the West, we elect legislative representatives at various levels, with the parliament as the highest. These remain in place for a fixed number of years and make universally applicable rules and laws to solve problems. The councils and their individual members have to prove themselves again and again by discussing a lot, giving interviews, making visits, etc., where they promise to put the problems which citizens are facing on the agenda to be considered while drafting or adapting universal rules.

Similar structures exist in the East, but the individuals are appointed on the basis of their expertise. Their appointment itself confers status. They also show up regularly, but do so when someone in their jurisdiction raises the alarm with a concrete problem. They address these problems using their recognized status and based on the situation of the moment. In China’s context, there used to be counters or mailboxes for messages or complaints to leaders. Now there are hotlines, either by telephone or online.

We can show this again with a graph.

.

Conclusion

For those who are not yet clear, we would like to end with emphasizing that in our view both forms of democracy are equivalent in the sense that they are both experienced as democratic within their own cultural context by an overwhelming majority of citizens.

The second thing we like to state is that it is rather impossible (or at least not easy) to merge these different forms of democracy in order to combine 'the best of both'. After all, you cannot just export the culture of one region to another. It is important to gain insight into the differences of other cultures. For example, you can try to implement an aspect of another culture that appeals to you in terms of your own culture.

This essay is not an exhaustive analysis of all forms of democracy in the world but explains there is not only one form of democracy and its manifestations are directly related to cultural dimensions.

The Chinese model is increasingly appreciated in the non-Western world, as China is the first non-Western nation having grown to the world’s second economy without an attempt to adopt Western values. An alternative and positive example for more particularist sphere cultures to which many nations in the non-Western world belong.

This is not to say that the other nations can just follow China's example. Specific culture, after all, is non-transferable. What other non-Western nations can learn from China is to regain respect for their own specific cultural values developing their own nation, including their own version of democracy.