Echoes Of Volatile And Delusive Memory: Challenging Historical Interpretations

Making sense of China by snapshots is impossible without watching the film

‘Scholars once thought secularization is an irreversible trend in the age of modernity,’ a note by Chinese sociologist Zhao Dingxin (赵鼎新) , Professor in Sociology at Zheijiang University and the University of Chicago when explaining the Daoist perspective that history does not progress toward some teleological terminus that can “lay claim to universal or eternal truths … because the significance and function of any causal forces invariably change with different contexts.”

The Daoist perspective stands rather in contrast with the essay “The End of History” written by American political scientist Francis Yoshihiro Fukuyama in 1989. Fukuyama mentioned that the triumph of the West, of the Western idea, is evident first of all in the total exhaustion of viable systematic alternatives to Western liberalism. ‘What we may be witnessing is not just the end of the Cold War, or the passing of a particular period of postwar history, but the end of history as such: that is, the end point of mankind's ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government.’

While Fukuyama’s perspective on a definite form of human government has been under pressure in recent years, the sense or impression of Western liberal democracy as ultimate governance for humanity lingers on through time in Western societies. With other forms of governance continued to be measured by the yardsticks of Western liberalism. And certainly other forms being debunked or criticized in any direction of their development, even rather opposite ones.

In recent months, the depiction of China in Western media has transcended its portrayal solely as an assertive economic power and authoritarian force with expanding global influence. It now encompasses discussions surrounding a perceived decline in its economy attributed to demographic aging and speculative economic policies. This broader portrayal has sparked various speculations within media regarding potential implications for China and its influence on the global economy.

Download paper as a PDF file here.

China has been under intense scrutiny in the Western world for several years now, owing to its unprecedented ascent in various spheres - economic, social, and political - over the span of just a few decades. However, the coverage of China in publications, op-eds, and news has predominantly been cast in a negative light, emphasizing an escalating trend toward authoritarianism and assertiveness.

While the Western world's interest in China has grown exponentially, the longevity of opinions and predictions has often proven to be limited. This trend is not new; the West’s perceptions of China have fluctuated over time, mostly based on highlights of isolated critical moments or shifts of political leadership. And other perceptions simply forgotten.

An interesting parallel of the volatility surrounding the understanding of realities about China today is the book ‘400 million Customers’ written in the 1930s by Carl Crow, US businessman in Shanghai. Depicting a vibrant and speculative business environment in China at the time with intriguing lessons ‘Doing Business in China’ to be learned, Crow also delved into his thoughts of cultural and geopolitical sensitivities. He was concerned about the escalating Japanese aggression in the 1930s, seemingly downplayed by others. He also strongly opposed the popular racist term "Chinaman" in vogue at that time. Not a completely new term at the time as similar expressions within the racist metaphor of Yellow Peril already appeared since the late 19th century.

Picture credit : ‘Four Hundred Million Customers: The Experiences - Some Happy, Some Sad - of an American in China and What They Taught Him’ (Amazon)

Carl Crow's business lessons and market descriptions were soon forgotten by the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937 and it wasn't until China reopened to the world in the late 1970s that foreign businesses had to reacquaint themselves from scratch again with the intricacies of Chinese business culture and environment. Occasionally leading to costly and challenging learning experiences.

“China : an ongoing film, replete with peaks and troughs”

China is a prolonged and dynamic societal and economic experiment since the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949. An ongoing film, replete with peaks and troughs marked by unprecedented achievements, excessive missteps, course corrections and deviations. But au fond with an overarching vision.

This formation has been characterized by a continuous series of reforms and policies tailored to specific stages of socio-economic development, while also adapting to external influences and changing circumstances. The all-encompassing objective of this ongoing endeavor has been to reinstate China as a prosperous and harmonious nation and society, commonly referred today to as the "China rejuvenation." A process having been steered under the leadership and governance of the Communist Party of China (CPC). The contemporary popular phrase “China Rejuvenation” should not be interpreted literally but more as reviving the essential core aspects of Chinese culture. More encompassing is the Chinese term 中国民族的复兴 (Zhōngguó mínzú de fùxīng), in broad sense ‘the renaissance of the Chinese people'

In broad sense, different consecutive phases in the ongoing film can be recognized. The periods of Deng Xiaoping’s Reform and Opening Up followed Jiang Zemin’s continued market-oriented reforms from the late 1970s to the early 2000s had economically been impossible to materialize without Mao Zedong’s rigid state-planned economy of industrialization from the 1950s to the 1970s. A period of sacrifices and hardship for the Chinese people in which China transformed from a rural economy to an industrial system at the size of France in just 30 years time with the support of sometimes called the world’s largest technology transfer in history from the Soviet Union to China.

Picture credit : ‘Soviet electrical engineer Zhuowugnodny explaining Ansteel Group workers how to use the blast furnace in 1953 (CEPR Technology transfer and early industrial development: The case of the Sino-Soviet Alliance)

The leadership eras of Deng Xiaoping and Jiang Zemin have generally been lauded in Western circles, notwithstanding moments of serious setbacks. However, they also brought about higher risks associated with speculative economies, inequality, pollution, and corruption, with the potential emergence of dominant industrial and market conglomerates. These challenges have especially gained heightened attention since Xi Jinping's leadership since the early 2010s. An era of augmented emphasis on regulatory oversight, the incorporation of high-tech and digital transformations, and sustainable and green developments.

Moreover, drastic and rapidly evolving changes in the external environment and the declining perception of China in the world (especially in the West) since the second half of last decade, along with its current substantial economic scale and global market influence, have become a pivotal consideration in shaping contemporary strategic vision and policy making in China. This includes a focus on matters of security, global diplomacy, and the establishment of new multilateral collaborative frameworks and developmental initiatives. Looking at international media and political discourse, it is obvious that these strategic policies are not universally embraced in the Western world. Xi Jinping's leadership era is frequently portrayed as a significant departure from the more appraised times of Deng Xiaoping and Jiang Zemin.

Attempts to elucidate China's development across various junctures within this narrative are often hindered by the (cultural) tendency to isolate specific events, temporal spans, or individual figures as mere snapshots. Snapshots often depicted in contrast with each other for for clear exposition. But thereby impeding a holistic understanding of why China undertakes certain actions or directions at different points in time.

This tendency confirms the cultural dimension of Specific/Diffuse. People from specific oriented cultures begin by looking at each element of a situation. Concentrating on hard facts, they analyze the elements separately, followed by comparison or viewing the whole as the sum of its parts. People from diffusely oriented cultures see each element in the perspective of the complete picture. All elements are related to each other and the whole whole is more than simply the sum of its parts.

Picture credit : The 7 Dimensions of Culture by Fons Trompenaars and Charles Hampden-Turner (THT Consulting)

“Beyond the popular timeline of the modern China film”

Grasping a nuanced comprehension of contemporary China necessitates transcending the boundaries of the comprehensive developmental narrative from 1949. It is imperative to acknowledge the profound influence of historical and cultural contexts on the China of today. But memories about China in the pre-1949 era and the enduring vitality of Chinese culture are scarce in the many international views and opinions portraying China today.

For a more comprehensive and cohesive level of understanding, one must rewind the cinematic reel further back in time. The early 19th century, specifically around the 1830s, may serve as an appropriate starting point, if only to keep the complexity of the movie narrative somewhat manageable.

From the 1830s to the 1940s, China grappled with a series of seismic upheavals on its soil, spurred by a weakening governance, internal rebellions and external intrusions by Western and Japanese imperial powers. Weakening governance and domestic rebellion had always been parts of Chinese history, the turns of dynastic cycles. But the unique difference at this historical period of time, in comparison with previous cycles was the overwhelming influence from abroad. This tumultuous period witnessed two Opium Wars with Britain, a litany of inequitable treaties, the incursion of the Eight-Nation Alliance (comprising Germany, Japan, Russia, Britain, France, Italy, Austria-Hungary, and the United States), two wars with Japan that resulted among others in the occupation of Taiwan, and numerous other instances of foreign subjugation and intervention.

Picture credit : “En Chine — Le gâteau des Rois et... des Empereurs” ("China -- the cake of kings and... of emperors"), a political cartoon in the "Le Petit Journal", a conservative daily Parisian newspaper (published January 6, 1898).

The pastry represents "Chine" (French for China) and is being divided between caricatures of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom, William II of Germany (who is squabbling with Queen Victoria over a borderland piece, whilst thrusting a knife into the pie to signify aggressive German intentions), Nicholas II of Russia, who is eyeing a particular piece, the French Marianne (who is diplomatically shown as not participating in the carving, and is depicted as close to Nicholas II, as a reminder of the Franco-Russian Alliance), and a samurai representing Japan, carefully contemplating which pieces to take. A stereotypical Qing official throws up his hands to try and stop them, but is powerless. It is meant to be a figurative representation of the Imperialist tendencies of these nations towards China during the decade.

Within this historical framework, the Qing Empire succumbed in 1912, leading to the establishment of the Republic of China under the leadership of the Kuomintang, the Nationalist Party of China. A period in which Chinese academics and industrialists excessively admired and adopted Western values as the only way to bring China forward. In contrast to the rising Communist Party of China (founded in 1921) of which a large number of members continued to adhere to Chinese traditional values with increasing popularity. The Shanghai massacre in 1927, also known as the April 12 purge marked a turning point during time. This violent suppression of the Communist Party (and leftist wings of the Nationalist Party), led by the conservative Kuomintang General Chiang Kai-shek, triggered a civil war between the Nationalists and Communists that persisted until 1949. A civil war which experienced intermittent pauses, characterized by a fragile and somewhat ambiguous collaboration between both parties as they confronted the Japanese invasion from 1937 to 1945.

The leader of the CPC, Mao Zedong proclaimed the founding of the People's Republic of China (PRC) on October 1, 1949. Simultaneously, the Nationalists retreated from the mainland to Taiwan in December of the same year, with Chiang Kai-shek designating Taipei as the temporary capital of the Republic of China (ROC), commonly called Taiwan in the West. This declaration came with an assertion of their government's status as the sole legitimate authority for the entirety of China—a claim still cloaked in ambiguity, as evident in Taiwan's constitutional context. Political parties within Taiwan maintain differing positions on territorial claims, adding further complexity.

At the inception of the People's Republic of China in 1949, the nation was wrecked. Yet, this moment marked the end of what is often referred to as the "百年国耻" or '100 years of national humiliation,' also known as China's century of humiliation. This period is deeply ingrained in the collective consciousness of China and Chinese values, and exerts a profound influence on contemporary governance and society.

“What to keep in mind watching the China film”

However, even when considering the 1830s as a starting point for the film, a comprehensive understanding necessitates a deliberate and thorough reminder of the actual integration of history and culture within China today.

Apart from historic timelines, the extent of homogeneity within Chinese (Han) civilization is a characteristic that cannot be understated. China has endured occupations, divisions, conflicts, and diverse forms of governance over millennia. Yet, the shared written language of characters since ancient times, thereby coupled with the rich legacy of historical records, has created a deeply rooted common identity with thriving dynasties in the past. This identity is founded on the shared practice of a common mode of communication, customs, beliefs, and traditions. It radiates a sense of homogeneity that permeates all facets of Chinese society and governance, a uniqueness in its scale and enduring continuity.

Picture credit : qi xna (Unsplash)

In many Western nations, portions of history have been distanced due to demographic shifts, social transformations, geopolitical dynamics, or alterations in governance. Some historical chapters in the West have become subjects of objective, detached analysis and scholarly studies, often disconnected from contemporary societal practices or emotions. In contrast, in China, children recite poetry from the Tang or Song Dynasties, which are over 1,000 years old, as if they were composed just a few decades ago. This enduring connection with the past reflects the deep roots of Chinese history and culture within the present-day Chinese society.

“The multifaceted complexity of historical interpretations”

Understanding a foreign land with its unique cultural, historical, and governance attributes goes beyond mere knowledge of past events. It entails grasping the interpretations and real-world implications of those events in contemporary societal, cultural and political settings.

Diverse nations and societies naturally have varied interpretations and timelines of history, shaped by selection, perspective, and the relative significance of historical facts and judgments. Geographical location, causal historical events, societal, political, and economic progress, all contribute to this evolution over time.

Cultural dimensions also plays a pivotal role in shaping the interpretation of history. Low-context cultures perceive history differently from high-context cultures. Collectivist cultures approach history distinctly in comparison with individualistic ones, as homogeneous societies do in relation to heterogeneous ones.

Cultures influenced by revealed religions over time tend to view history through a different lens, including contexts of absolute revelations when interpreting the past. In such cultures, historical events and ideas are seen as products not only of natural reasoning but also of divine intervention. This cultural tendency leads to continual reevaluation and reinterpretation of history to align absolute revelations with contemporary consciousness. Christianity and Islam are examples of revealed religions that exhibit this characteristic.

In East Asian cultures like China, revealed religions have had limited influence historically. History, an authority in itself, serves as a normative legacy, guiding societies. Philosophical doctrines like Daoism, Buddhism, and Confucianism, largely devoid of revealed divine agencies, address matters related to natural existence, ethics, and the human condition, in ways that prominently involve the teaching and learning of history.

The Chinese proverb "溫故知新 wēn gù zhī xīn" or "Review the Past and Learn the New," derived from the teachings of Confucius, reflects the importance of historical understanding. It underscores the value of cherishing old knowledge while continually acquiring new insights, as a pathway to becoming a teacher and imparting wisdom to others.

These multifaceted and culturally embedded complexities contribute to the vast divergence in historical interpretations. Consequently, projecting one's understanding of another country's history through the lens of one's own cultural and historical context does not necessarily lead to a more profound comprehension of that nation. Often on the contrary.

“History : a victim during times of conflict”

The practice of projecting another nation’s history through own lenses is particularly evident during geopolitical tensions or transformation, where historical interpretations often serve as tools for justifying political claims and shaping social narratives. During periods of conflict, historical interpretation is particularly vulnerable to distortion, omission, or even outright fabrication for the purpose of advancing political agendas of conflict. Not surprisingly as conflicts often stem from divergent interpretations of history. Thereby an ‘easy victim’ to validate the policies of the conflict.

Negative perceptions of China in the West often lack historical context, reducing complex issues like the Taiwan conflict to simplified, often cramped narratives. Accusations of China's aggressiveness against an independent, sovereign nation Taiwan overlook historical nuances and facts such as the sovereignty status associated with Taiwan. The One China policy, adhered to by a majority of nations worldwide since about half a century, endorses Beijing as the sole legitimate governance authority over sovereign Chinese territory, inclusive of Taiwan. Nevertheless, within bilateral joint communiqués, strategic ambiguity is maintained, a stance that often serves the interests of the foreign policy of the United States and its allies.

Also influencing current negative perceptions of China regarding Taiwan is the ‘fabrication’ of the ‘China will invade Taiwan during the next years’ narrative since March 2021 when US Admiral Philip Davidson testified before the Senate Armed Services Committee with the warning that China could invade Taiwan in the next six years based on his gut feelings. This speculation was in no time followed by a surge of other timeframes with the Economist magazine even dubbing Taiwan as the “The Most Dangerous Place On Earth” on their May 2021 edition cover. Since then one of the prevailing ‘China threat narratives’ within Western discourse, encompassing diplomatic and political provocations, and, notably, policy moves towards military armament by Washington with respect to Taiwan.

Picture credit : The most dangerous place on Earth, The Economist (May 1st, 2021)

Instead of a ‘sudden’ aggression against The Republic of China (Taiwan), it is imperative to recognize that the aspiration for reunification has consistently featured as a core objective for every Chinese leader since 1949. A recognition usually dismissed in the mainstream perception.

Another example of history being victim to validate contemporary opinion and policy making is carbon emission polution. China is often impugned, especially in western media, as being the main responsible actor of world’s current state in carbon emission pollution. While China is the largest carbon emitter today with 30% of the total emissions in 2021, when we include the context of historic cumulative emissions having lead to the current state of the climate, data are rather different. From the industrial revolution almost two centuries ago, the United States has contributed about 25%, the EU region 22%, and China 13% of the cumulative greenhouse gas emissions.

And not only the context of history is often omitted in accusatory opinions concerning carbon pollution, contexts of carbon emission outsourcing and consumption over time are usually not considered in the equation aside production. Also the perspective of ‘carbon emission per capita’ shows a different perspective.

Climate change is a complex challenge facing humanity. Omitting historical and other contexts decrease common chances of achieving responsible and inclusive consensus and plans of action.

“The convenience of fabricating or dismissing history”

Recognizing each other's interpretations and historical contexts is paramount for nurturing mutual understanding, fostering collaboration, or resolving conflicts.

Such considerations can coexist with critical analysis and robust debates regarding their appropriateness and relevance to current circumstances and developments. Over recent decades, geo-economic and geo-political dynamics have undergone significant transformations, primarily driven by shifts in economic scales, interdependence, and global interconnectedness among nations.

For example, one might contemplate whether China should continue to invoke a "victim-like" narrative (in Western eyes) based on the "century of humiliation" or its status as a developing nation, even as it holds the position of world's largest trading nation and second-largest economy, excelling in cutting-edge technologies.

Or one could critically assess instances where some former colonial powers in Europe have issued official apologies for their colonial past. Such apologies can be viewed as gestures of acknowledgment, but also as potential attempts to distance themselves from the enduring consequences and responsibilities of that history (in view by others), which still affect some former colonies to this day. The encompassing process of decolonisation is still going in different parts of the world.

However, an inadvertent disregard for historical understanding (historical estrangement) or a deliberate omission of such considerations can foster misunderstanding and heightened tensions. It's worth noting that while American, British, and other Western naval vessels have routinely traversed the Taiwan Strait near the Chinese coast since years, these actions bolster China's rationale for incorporating historical insights into contemporary policy decisions. Relevant historical episodes, such as the Eight-Nation Alliance's violent invasion at the dawn of the 20th century or British gunboats navigating the Yangtze River in 1839 to enforce the opium trade, can resonate with contemporary views.

Furthermore, China's rationale is informed by the presence of over 300 U.S. military bases and installations in East Asia, encircling its sovereign territory. A China encirclement or containment policy by the United States already in place for two decades since the turn of the century.

It is of crucial importance to remain cognizant of the ongoing process of shaping a 'history-in-the-making' or fabrication in the West by policy influencers or makers, which characterizes China as a sudden aggressive authoritarian threat to the liberal democratic world. Fabrications which are deliberately distorting people’s views on reality through media. These narratives often lack substantial historical and cultural context. Instead they serve to legitimize and reinforce geopolitical ambitions and policies, rendering them particularly susceptible to escalation during times of conflict.

And when escalations do occur, these fabrications of history swiftly find their way into historical accounts, ultimately obscuring the complex historical context of the conflict.

An example of the wholesale omission of historical context in major conflicts can be observed in the immediate neglect, within mainstream media and political discourse, of the three-decade-long geopolitical chronology between NATO and Russia leading up to Russia's invasion into Ukraine in February 2022. Prominent political leaders and scholars in the West had, for years and decades, sounded warnings regarding the eastward expansion of NATO in Europe since the early 1990s. Similarly, the significant U.S. involvement in Ukraine from the early 2010s through actions like regime change and militarization has largely been disregarded since Russia's intervention. Additionally, NATO’s real intentions of the Minsk agreements (2014 and 2015) to gain time and Russia's repeated cautions about NATO's expansion into Ukraine, considered as crucial red lines, have been dismissed by large as well.

Upon Russia's intervention in Ukraine, the Western narrative immediately narrowed to a single depiction of the conflict as 'unprovoked', with Vladimir Putin cast as the malevolent, imperialist force to be defeated by any means necessary. Any historical geopolitical context related to the conflict has abruptly been eradicated since, and anyone daring to raise a single question is swiftly labeled as being in the enemy's camp. Not questions or statements concerning possible endorsement of the invasion but questions or quests for considerations about the narratives having lead to the invasion.

The phenomenon of truth becoming the first casualty in war is not a novelty but it is essential to resist the complacency reflected in the oft-cited phrase, "The only thing we learn from history is that we learn nothing from history." Examining the decades long geopolitical prelude prior to Russia’s invasion in the Ukraine reveals a parallel in the fabrication of contemporary China narratives with regard to among others the Taiwan conflict with diplomatic provocations or military armament policy proposals for Taiwan coming out of the West. Historic contexts to the conflict have increasingly been omitted over the years in media and political arenas. And again warnings from academics and experts to be more contextual, these cautionary voices are marginalized or disregarded, with some individuals labeled as sympathetic to the Chinese perspective. Similar developments again approaching critical red lines, vulnerable for escalation.

While the capacity to learn from history is undeniably present, the question that lingers pertains to whether people are genuinely inclined to draw lessons from history when it comes to the realm of conflict politics. When historical interpretations and legacies are overlooked or manipulated instead of being considered, even critically, it often signals deeper conflicts in contemporary geopolitical or geo-economic landscapes. Exploiting history for the sake of contemporary circumstances.

“The role of history in China today”

The impact of history on China today, its conduct, and actions is profound. China's historical trajectory is naturally marked by periods of disruption, separation, and occupation over millennia. And, it is equally characterized by numerous flourishing eras, marked by economic, cultural, and social achievements. Of paramount importance is the fact that China has maintained a cohesive politico-cultural identity with remarkable homogeneity since ancient times.

Most of the Chinese people take great pride in their historical legacy, which serves as a bedrock of Chinese culture. This sense of pride is bolstered by the unprecedented economic growth and improvements in living standards witnessed in recent decades, as well as China's notable contributions to the world, exemplified by initiatives like the Belt and Road Initiative. Consequently, China and its people believe in their place at the forefront of great nations in the world.

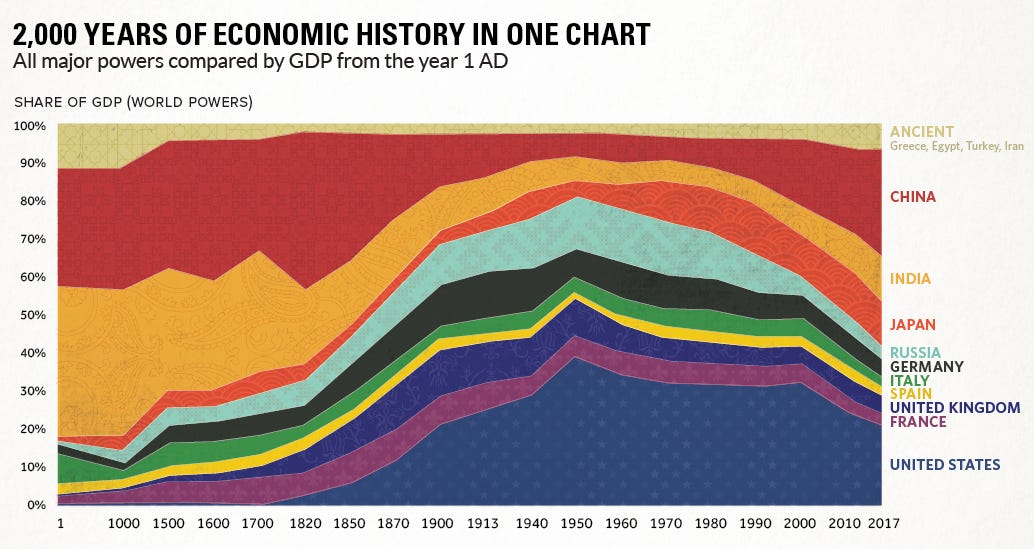

The "Century of Humiliation" from the 1830s until the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949, coupled with the precipitous decline in the economy during that period, is considered a divergence when contrasted with China's economic prowess for the majority of the previous 1800 years. Historically, China, along with India, and presently with the United States, has been one of the largest and most thriving economies in the world throughout history.

Picture credit : 2,000 Years of Ecomonic History in One Chart, Visual Capitalist, Sept. 8, 2017

Recent headlines in Western media and political discourse have often depicted China as pursuing exclusive domination and hegemonic expansion. However, these interpretations are largely misguided and result from viewing China's actions through own Western historical lenses (that are not always pretty).

China's fundamental objective, as articulated by its leadership since the founding of the People's Republic, centers on the renaissance of China and its values. This entails restoring China to its rightful place as a prosperous and influential global nation, underpinned by three main objectives: advancing economic and societal well-being, rectifying historical injustices stemming from foreign invasions and civil wars prior to 1949, notably in the context of reunification with Taiwan, and attaining a commensurate voice and influence in the global economy and multilateral institutions.

While the objectives of achieving economic and societal growth are straightforward, the pursuit of historical justice seeks to address the legacies of perceived "injustice" resulting from decades of foreign invasions and civil conflict. Notably, it encompasses the objective of reunification with Taiwan.

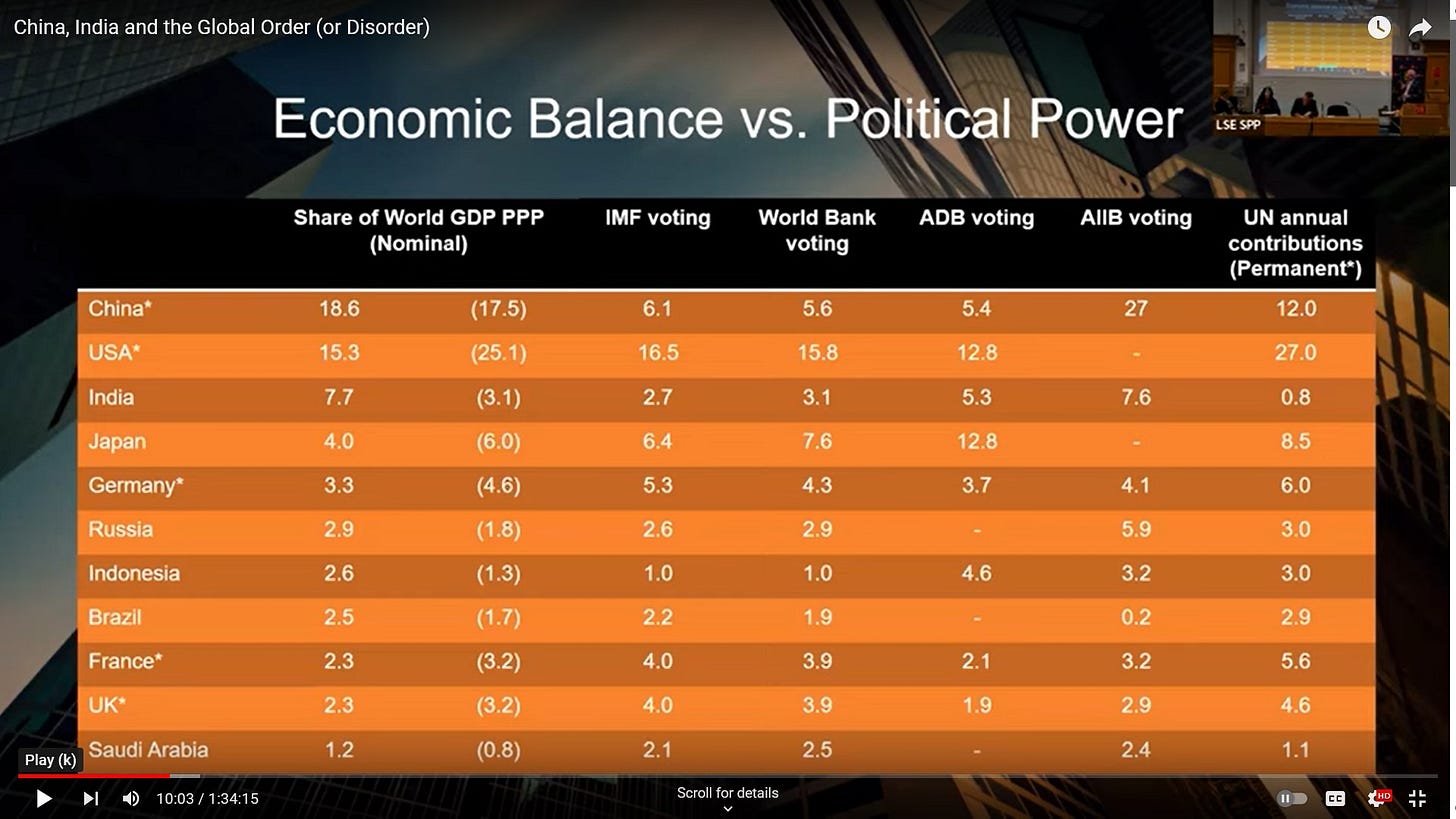

The third condition, which concerns China's rejuvenation, relates to developing a proportional voice and influence in the global economy and international institutions. This is in acknowledgment of China's status as the world's second-largest economy and a pivotal global player.

Despite significant shifts in the global economic landscape in recent decades, many of these international institutions have retained their Western-centric political power and leadership. With large disproportions between the current economic balance and political power in various multilateral institutions.

Picture credit : China, India and the Global Order (or Disorder), LSE School of Public Policy December 1, 2023 (YouTube)

And despite the new economic landscape, the leadership of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank remain exclusively being led by Europeans and Americans, respectively, since their founding in 1944 at the Bretton Woods conference.

China's ambitious aspirations have not found favor in the political circles of Washington and its allies. China is frequently accused of flouting the "rules-based international order," a term widely employed by the political Western hemisphere.

For some, the "rules-based international order" represents a concept rooted in international law, characterized by principles of democratic governance, economic openness, and the rule of law. It embodies values such as the protection of freedom, equality, human rights, and security, transcending the confines of narrowly defined international laws. Some call it “Western liberal values”.

Another view of the "rules-based international order" is being this concept a ‘convenient’ alternative to the established international laws, such as in the United Nations. This has also led to the questioning why the United States and its allies are increasingly resorting to the rules-based international order. A questioning with critical notes that the rules-based international order is America’s way of asserting legal authority in line with their national or international interests. An authority with ‘rules’ of indeterminate nature subject to a higher risk of speculation or manipulation. This view is supported by the United States having abstained from ratifying several significant multilateral treaties and are not signatory to numerous international humanitarian, war, and criminal laws and courts.

It is in this modern historical sphere that China has embarked on a long-term strategy to establish alternative multilateral institutions, frameworks, and mechanisms in collaboration with other nations. This initiative aims to reduce China's reliance on U.S. or Western-dominated institutions, mechanisms and ‘orders’ that could undermine, restrain, or inadequately represent China's position as a significant global player with the right to grow. Examples of these endeavors include the multilateral organizations BRICS (2010) and SCO (Shanghai Cooperation Organization, 2001), as well as the Belt and Road Initiative (2013) and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB, 2016). This proactive stance by China signifies its commitment to co-shaping the future international landscape while reducing dependency on existing Western-led structures.

Above trends signal a growing division between the stronger adherence to the ‘rules-based international order’ in Western political arenas on one side and the growth of new, alternative multilateral structures along with stronger ‘non-western’ voices in original multilateral institutions such as the United Nations on the other side.

Picture credit : Jiefang west road, Changsha city, Hunan province; Rachel T (Unsplash)

Through a cultural lens, this development is also a confrontation between universalist and particularist cultures. A divide of cultural interpretations how rules and order are being dealt with in specific situations. With growing senses of overall morality and righteous as references in universalist societies while particular contexts of circumstances and relations play important consideration in rules and order perceptions in particularist societies.

Historical interpretations : a double-edged sword

History, prevalent in every nation, serves as both a legacy and a burden, its narratives etched within cultural, social, economic, and political realms of specific historical events. As these spheres evolve, so do historical narratives, shaped by selective memory that highlights resonating aspects while sidelining others.

According to late historian Hayden White, history is shaped on both sides of barricades, reflecting multivoicedness and plurality. Historical accounts offer dignity and identity to some but disgrace to others, their truth contingent on community, contemporaneity, and the interests of favored groups. White also indicated “What we postmodernists are against is a professional historiography” and his perspectives underscore the delicate debate between historians and the philosophers of history.

The Daoist perspective of history as introduced at the beginning of the essay (Zhao Dingxin) of not being an irreversible trend towards a terminus claiming universal truths in contrary to the belief of some modern scholars.

Zhao furthermore refers to 老子 (Lǎozi), Chinese Philosopher (6th century BC), who wrote in the Tao Te Ching “the Dao that can be stated cannot be the universal (or eternal) Dao” because the concrete circumstances of existence are always in flux.

In Laozi’s perspective, history is not a paradigm of historical progression as rooted in Christian eschatology, focusing on the ultimate destiny of individual souls and certainly also of the entire created order. In contrast, history within Daoism is viewed through the basic principle of 反 (fǎn) or reversion. Anything, including history that develops more extreme dimensions will invariably revert to opposite dimensions.

In light of this principle of reversion, the interpretation of history necessitates a sense of humility, avoiding a delusion of upholding the rationale of history through revealed religious progression or morality. Zhao views such humility as an increasingly “rare trait” and “even scarcer within cultures dominated by a teleological comprehension of history.”

The principle of reversion also reminds humanity about the multifaceted interplay of interpretations of history, the large variety of diversified modes regarding historical interpretations. Instead of linear projections of future’s history or thereof mirrors of the past.

Understanding diverse historical interpretations is crucial for nations to comprehend their contemporaneity, relations with others, and objectives. History can serve as a tool for learning, self-improvement, and identity, yet it can also foster estrangement. Recognizing disparities in interpretations aids mutual understanding but can also lead to conflicting views when imposing one's historical narrative template on others. Assuming that others will behave and act similarly to patterns observed in own history.

In realms of conflict, history wields great power as a tool for polarization. By selectively omitting, emphasizing, or manipulating historical narratives, it can be weaponized to escalate conflicts, deepen divisions, and promote particular interpretations that align with the agendas of one side.

Different countries develop their views of history through distinct paradigms based on epistemology, ontology, and axiology, which encompass how people perceive the origins and sources of historical knowledge, what aspects of history are considered meaningful or true, and what ethical values shape their interpretation of historical events. These paradigms create unique lenses through which history is perceived.

Fully comprehending or empathizing with the historical interpretations of other cultures and nations is next to impossible for an outsider, given the deeply ingrained nature of these paradigms in a culture and its history. Let alone developing historical empathy from distinct cultures and societies. This makes it all the more important to be conscious of the existence of divergent historical paradigms, rather than imposing one's own templates or empathy onto the history of others.

Through a Chinese lens, two idioms carry significance in acknowledging this complexity. "求同存异 qiú tóng cún yì " (seeking common ground while reserving differences) underscores the complexities and sensitivities of differing paradigms and the importance of collaborating on shared responsibilities and challenges. "和而不同 hé ér bùtóng" (seeking harmony but not conformity) from Confucius emphasizes the need for peaceful coexistence while respecting differences in historical and contemporary interpretations. Confucius then thoughtfully continues “小人同而不和xiǎo rén tóng ér bù hé”, the villains are the same but not harmonious.

Fragmenting China's history and contemporary context through one's own historical paradigms can be detrimental to achieving a broader understanding of China or fostering collaboration.

Picture credit : People walking down a street in Beijing, Jean Beller (Unsplash)

The configurations of historical paradigms evolve over time, and it's possible for sensitivities to shift toward greater common ground and empathy. However, in times of conflict escalation, there is often limited time for such evolution. Historical contexts frequently play a fundamental role in the root causes of conflicts and the core interests of adversaries. Instead of disregarding history during conflicts, it is the responsibility and art of (diplomatic) conflict resolution to consider adversarial historical interpretations, aiming for a consensus to end the conflict or at least prevent its escalation.

Regrettably, a responsibility and human art, especially in diplomacy and leadership, that is greatly absent in contemporary times. Dire times of growing conflicts and escalations desperately require these human attributes with regard to the consciousness of significantly different historical interpretations.

A basic human necessity instead of trying to deal with the perplexity : Why can’t they not be more like us ?