Bandung: From Spirit to Compass

Why a 70-year-old communiqué is essential for navigating the emerging multipolar world order

In the mid-1990s, I was living in Jakarta, working on my Master’s thesis—a feasibility study on the cocoa beans market in Indonesia for one of world’s largest family-owned multinational agribusinesses based in the United States. On weekends, my friends and I would often try to escape the heat and traffic of Jakarta—the constant hustle of the “Big Durian”—by heading to the cooler, greener highlands of Bandung. At the time, the 150-kilometer journey could easily take four to five hours by car, depending on traffic—if you were lucky enough to even get out of the city. Today, a high-speed rail connects Jakarta and Bandung in just 45 minutes.

The 1990s are often considered a decade of extending and deepening globalization, and it was during this period that I also visited Beijing and Shanghai for the first time. Asian economies were on the rise, increasingly viewed by Western corporations as attractive hubs for manufacturing and resources—driven low production costs and regulatory environments more permissive than those back home. And they weren’t just production hubs; the Asian economies were also emerging as promising new consumer markets. In those days, an important conference held four decades earlier in Bandung felt like a distant historical footnote—its relevance overshadowed by the dynamics of globalization.

This week marks the 70th anniversary of the first Asian-African Conference, more commonly known as the Bandung Conference. From April 18 to 24, 1955, representatives from 29 Asian and African governments gathered in the Indonesian city of Bandung to discuss global peace, its role in the Cold War, economic development, and decolonization. Their goal: to promote mutual interests and foster cooperation among newly independent nations. The gathering brought together influential figures such as China’s Premier and Foreign Minister Zhou Enlai, Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser, and the host, Indonesian President Sukarno. Together, the 29 countries represented a population of 1.5 billion people—over half of the world’s population at the time.

Picture : Delegations held a Plenary Meeting of the Economic Section during the Bandung Conference (Wikipedia)

The conference published a joint communiqué on its final day, concluding with ten guiding principles for international peace and cooperation—known as the Dasasila Bandung (literally, the "Ten Principles or Precepts of Bandung"). These moral precepts reflected the shared aspirations of newly independent nations to build a more just and equitable world order, rooted in mutual respect and non-alignment. The principles were:

Respect for fundamental human rights and for the purposes and principles of the United Nations Charter.

Respect for the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all nations.

Recognition of the equality of all races and nations, large and small.

Non-intervention in the internal affairs of other countries.

Respect for each nation’s right to self-defense, individually or collectively, in accordance with the UN Charter.

Avoiding collective defense arrangements used to serve the interests of major powers, and refraining from exerting pressure on other nations.

Refraining from acts or threats of aggression or use of force against any nation's territorial or political independence.

Peaceful resolution of disputes through negotiation, mediation, arbitration, or other means consistent with the UN Charter.

Promotion of mutual interests and cooperation.

Respect for justice and international obligations.

The term Dasasila originates from Sanskrit (दसशील) where dasa means “ten” and sila refers to “morality,” “virtue,” or “right conduct”—concepts often associated with ethical teachings in Buddhism. The ten Bandung precepts drew from a range of philosophical and political sources. They echoed elements of Indonesia’s national ideology, Pancasila (literally “five principles”); China’s Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence (和平共处五项原则), also known as Panchsheel in Hindi, which were jointly articulated with India in 1954; and the foundational ideals of the United Nations Charter.

You can read the full Final Communiqué of the Asian-African Conference of Bandung (April 24, 1955) [here]

The spirit of the Bandung Conference lived on for a few years through the establishment of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) in 1961 and the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) in 1964. While NAM advanced a political agenda centered on peace and neutrality amid the Cold War, UNCTAD aimed to chart a development path for the Global South, better known at the time as the Third World—both embodying what came to be known as the Bandung Spirit.

Although neither the United States nor major European powers—particularly former colonial states like the United Kingdom, France, the Netherlands, and Belgium—publicly opposed the Bandung Conference or its Ten Principles, they viewed it with considerable suspicion. The gathering’s anti-colonial tone and call for non-alignment challenged their lingering imperial interests. In response, Western powers adopted a mix of diplomatic skepticism, covert efforts to curb the conference’s influence, and ideological resistance to its neutralist and decolonial stance.

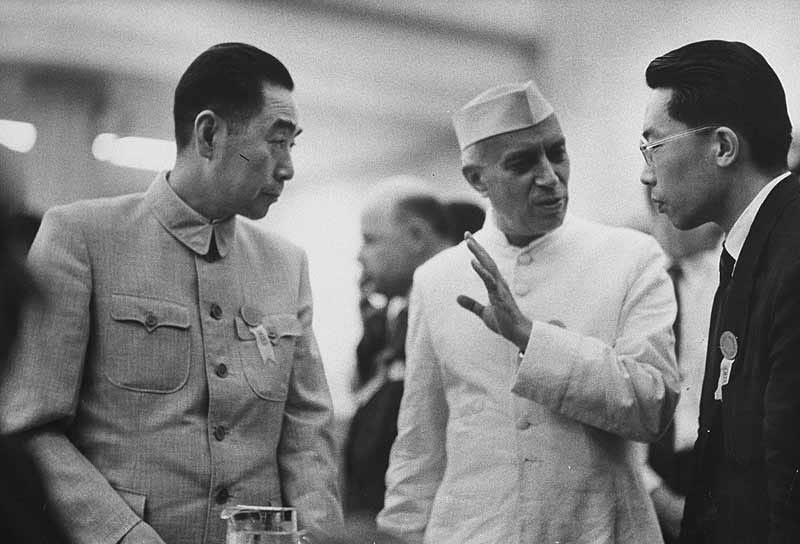

Picture : India's first prime ministerJawaharlal Nehru and China’s Premier and Minister of Foreign Affairs Zhou Enlai (iNews)

For decades following the Bandung Conference, and even up till today, its principles have largely been absent from multilateral institutions and global policy discourse. Former colonial powers and dominant geopolitical actors continued to exert control over Third World countries—extracting natural resources, agricultural goods, and mineral wealth, while retaining high-value processing and manufacturing within their own economies. Low-cost, labor-intensive, and environmentally damaging industries were often outsourced to the developing countries, reinforcing systemic economic dependencies. Simultaneously, covert and overt interventions—ranging from regime changes to proxy wars—ensured continued influence over post-colonial states.

These asymmetries became more entrenched after the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s, when the United States assumed the role of unchallenged global hegemon. Under the expanding wave of globalization, multilateral institutions like the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund—imposed economic and political conditions on developing countries. In return for loans or financial assistance, these institutions often demanded liberal democratic reforms and market liberalization aligned with Western models, reinforcing a framework in which the Global South’s agency remained constrained by the rules and interests of the dominant powers.

Through Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs), countries in Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia were required to implement sweeping neoliberal reforms—including democratic governance, privatization, trade liberalization, and cuts to public services—in exchange for financial assistance. These measures often resulted in economic hardship, weakened state institutions, and social unrest, while making recipient countries more dependent on Western markets and capital flows.

The repercussions of Western-led financial frameworks became evident during the Debt Crisis of the 1980s—often dubbed “The Lost Decade”—which engulfed over 40 countries, primarily in Latin America, but also in Africa and Asia. The pattern repeated itself in the 1997–1998 Asian Financial Crisis, when Thailand, Indonesia, and South Korea suffered massive capital flight, currency collapses, and deep recessions. Although the IMF’s interventions aimed to restore stability, the required austerity measures and structural reforms—criticized by many observers—exacerbated social inequality and prolonged economic recovery.

Likewise, China’s Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence, a base for the Bandung principles, have usually been dismissed in Western political discourse as mere propaganda—portrayed as incompatible with the dominant worldview of liberal universalism that framed the West’s global leadership.

Nonetheless, the 1955 Asia-Africa Conference marked a turning point for China, signaling its emergence from the diplomatic isolation it had faced since the 1949 revolution led by the Communist Party of China (CPC). China’s involvement in the Korean War (1950–1953) and the Western-led embargo that followed had left it largely cut off from the international community, particularly the West.

Bandung came just a year after two significant diplomatic breakthroughs in which China was involved. In 1954, China signed the Panchsheel Agreement with India—a border and trade accord in which the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence were formally articulated for the first time. That same year, China’s Premier and Minister of Foreign Affairs Zhou Enlai played an important role at the Geneva Conference, where China joined the United States, the Soviet Union, Britain, and France in negotiating settlements to the conflicts in Korea and Indochina. These talks resulted in a temporary peace across parts of Asia, halting open hostilities in Korea and securing a ceasefire in Vietnam and Laos—though this peace would end some years later when the United States escalated its military involvement in Vietnam.

Although many participants at the Bandung Conference viewed China as a looming “red threat”—with some heads of state reportedly instructed by Washington to oppose Beijing at every turn—Zhou Enlai defused much of the tension. In his opening speech, he declared that China had come “to seek unity and not quarrel... to seek common ground and not to create divergence.” His calm, measured tone, along with his diplomatic charisma and eloquence, stood in stark contrast to the suspicion many had arrived with.

What truly distinguished Zhou Enlai at Bandung was not just his opening remarks but his ability to navigate complex and contentious issues with humility and moderation. He helped broker consensus in heated debates, including those over the participation of certain nations in U.S.-led military alliances—such as SEATO and CENTO—which involved countries like Turkey, the Philippines, Thailand, Iran, and Iraq. Another flashpoint was the interpretation of “peaceful coexistence,” a concept central to China’s foreign policy but contested among delegates. Both issues, closely linked in their ideological underpinnings, were ultimately addressed in the final communiqué, thanks in part to the active engagement and negotiation led by the Chinese delegation.

Picture : China’s Premier and Minister of Foreign Affairs Zhou Enlai opening remarks at the Bandung Conference (China Daily)

Zhou’s diplomacy at Bandung won him widespread respect. Roeslan Abdulgani, the conference’s Indonesian secretary-general, later recalled Zhou as “moderate and engaging,” noting that “the People’s Republic of China no longer appeared in their eyes as a dangerous ‘Giant Dragon.’”

Read more about how different nations and cultures view and interpret history, especially between the West and China in China21 Journal essay “Echoes Of Volatile And Delusive Memory: Challenging Historical Interpretations”

Yet Zhou’s growing stature in those years alarmed Washington. U.S. officials feared his charisma and persuasive skill could sway Asian and African leaders toward communist-aligned positions, undermining American interests. Just a week before the conference, on April 11, 1955, the Kashmir Princess—an Air India chartered plane carrying Chinese delegates from Hong Kong to Jakarta—exploded mid-air, killing 11 passengers. Zhou, the intended target, had altered his travel plans at the last minute and was not on board. Investigations implicated Kuomintang agents, reportedly with tacit backing from U.S. intelligence, in an assassination attempt designed to disrupt China’s role at Bandung—a plot Washington has never officially acknowledged.

China’s success at Bandung enabled Beijing to forge diplomatic ties across Asia and Africa in the years that followed—an outreach that proved especially crucial after its split with the Soviet Union in the 1960s.

Fast forward to the 2020s, the rapidly expanding BRICS group is sometimes portrayed as the heir to the “Bandung Spirit” but this comparison is not accurate. The 1955 Bandung Conference emerged as a unified political voice for newly independent nations within multilateral forums like the United Nations, at a time when most of its participants lacked significant economic power. BRICS, by contrast, was formed in 2009 in the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis, driven primarily by a desire for greater collaboration and coordination between rising large countries which were not invited or represented in existing multilateral forums such as the G7. As India’s External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar bluntly put it last year , “Why the club? Because there was another club! It was called the G7 and you would not let anybody else into that club. So, we go and form our own club.”

If any modern institution more closely mirrors Bandung’s political ethos, it is ASEAN—the Association of Southeast Asian Nations—founded in 1967 to foster regional solidarity, peace, and cooperation among its sovereign states.

Compared to the 1950s, the 2020s are a different era. In the decades following Bandung, the United States and its allies exerted overwhelming economic and political dominance, shaping policy and discourse within multilateral bodies—especially financial institutions like the World Bank and IMF. Yet Bandung participants and other developing countries did not sit idle; they studied Western models of governance and development, adopting what served their needs and forging unique paths based on own culture, history and society where necessary. Some succeeded more than others, often those who did not fully subjugate to Western imposed templates but charted their own tailored course of development.

China is a leading example. For decades, Western policymakers believed that liberal democracy was the sole universal route to economic prosperity and social progress for any nation in the world. China has proved this assumption false, crafting a distinctive development model rooted in its system of governance and cultural values. Over the past few decades, China has transformed into a global economic and industrial powerhouse, asserting growing geopolitical influence within the international world order. Its long-term strategy has emphasized sovereignty and self-reliance, both in security measures and developing critical supply chains.

China’s—and also India’s—distinctive development models, informed by their unique cultural traits and historical legacies, have recently inspired other nations in the Global South to push back against decades-long patterns of external political influence and resource exploitation, and to chart their own paths forward.

Read more about the different cultural values between the West and China that shape diverging societal behaviors and world views in China21 Journal essay “it’s the culture, stupid”.

A quick search for “globalization” in Google or international media often yields the same verdict: it’s over. Indeed, the era of globalization as defined—and dominated—by transatlantic economies has drawn to a close. Yet we’re witnessing the rapid and increasingly turbulent rise of a new globalization, accelerated by Washington’s global tariff wars and characterized by intensified and diversified economic linkages, trade relations, and capital flows, and an expanding web of multipolar institutions at regional and sub-regional levels that shape both economic and security governance.

The changing landscape of globalization does not evoke a revival of the ‘Bandung Spirit’; instead, the Dasasila Bandung—the ten Bandung principles—increasingly serves as a vital compass to carefully navigate the current, sometimes stormy, transitions in the emerging multipolar world order. There is a growing recognition that no single, universal template can guarantee development or prosperity for all nations. The compass urges to prioritize mutual respect, non-interference, and cooperative development. As power diffuses and global networks expand, these principles can guide both emerging and established actors toward a more balanced, inclusive world order and a new phase of globalization.

I still remember one early morning in the 1990s, back when I was working on my thesis in Jakarta. We were all asked to the airport to greet the U.S. corporate board—silver-haired, Florida-bronzed gentlemen in crisp white polo shirts—stepping off their private jet. They had flown in to inspect the company’s agricultural operations, which were largely devoted to extracting Indonesia’s natural resources for export to the U.S. and a handful of friendly allied First World markets.

That era has come to an end…

April 24, 2025

Gordon Dumoulin

Sources :

Wilson Center Digital Archive | Bandung Conference, 1955

Luxembourg Centre for Contemporary and Digital History | Bandung Conference

Bandung + 60 | The 1955 African-Asian Conference, 60 years later

‘Globalization isn't over; it's just beginning’ by

(Global Times, April 19, 2025)The Bandung Conference: Historical Memory and Vision (Valdai Club, April 18, 2025)

‘The Spirit of Bandung’: The Past and the Future (Valdai Club, April 21, 2025)

Thank you for this great explanation of the spirit of the Bandung and it's connection to ASEAN and BRICS. Perhaps more importantly, thank you for the wonderful account of the great Zhou Enlai!

Thanks for recalling the Bandung spirit. A truly historic act of newly emerging nations.